Chapter 2: Industrialization: Formation of the Heartland

The Midwest, as defined by the Ohio River and the Great Lakes.

It wasn’t until the industrialization of the region that it was given a name to differentiate it from the rest of the western part of the country; the term Midwest did not appear until 1880’s or 1890’s (Shortridge) and the ‘borders’ of this region have changed many times. For our purposes, we will define the Midwest by the region bounded by the Great Lakes and the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, for it is within these states that heavy industry was established on a large, unprecedented scale.

The region’s convenient location, near the more populous Northeast and Middle Atlantic sections of the county, with its abundant waterways, fertile soil and natural resource deposits, made it ideal for settlement and industry. The location became especially relevant in terms of manufacturing during the Civil War, for the Midwest was most convenient to ship from.

While Europe was ahead in terms of the establishment of large-scale industry, it was America that prompted the sleek, functional aesthetic of the modern factory, its roots appropriately planted in the Midwest, a region known for its rationality and self-reliance. From early grain elevators to the vast, integrated industrial complexes of the early 20th century, industrialization intensely transformed every aspect of life. “[The factory] is the only type of contemporary architecture which shows no uncertainty, indecision, or traces of a once-universal eclecticism” (Nelson 12), and while it was highly influential to architectural movements, it was also influential to art, culture and society in general. Considering this, “the factory is no less significant than the medieval cathedral, which also in its time reflected the dominance of another force of worldwide importance” (Nelson 13). Industrialization also spawned urbanization, requiring housing and commercial districts to be constructed near industry and resulting in density and necessitating urban planning.

Timeline of industrialization in the Midwest.

1800-1850

During the rise of the Industrial Revolution in Europe, the Midwest was primarily rural- it was a landscape dotted with wooden grain elevators, silos, and the industrial buildings associated with agricultural production. Industrialism as a changing way of life was not yet a concept, but Americans were determined to control industrialization, so as to not allow the ‘over-civilization’ which was occurring in Europe. The founders desired a ‘Middle Landscape’, a settlement somewhere between uncivilized and industrialized, but failed to establish where and when to draw the line.

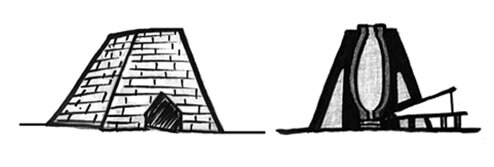

Early, wooden grain elevators used vernacular materials and massing. Situated near railroads, the buildings often generated entire town plans.

Early grain elevators were vernacular structures, built using locally sourced timber and assemblies of shapes and massing common in barn and farmhouse design. These grain elevators were the tallest structures around, a feature magnified by the miles and miles of flat land surrounding it. They were located along railroad tracks, and often became the landmark that established the town, thereby generating the entire town plan. This ‘lonesome’ grain elevator is a strong representation of the ‘Middle Landscape’- a small business surrounded by both agricultural and wild landscapes, supporting a small, civilized population. Despite early developments towards industrialization, the region was proud of its agricultural roots, and believed that agriculture would continue to be the ticket to prosperity, and that other goods would continue to be imported from Europe.

The first phase of industrialization consisted of major transportation advancements in the form of railroads and canals that enabled trade throughout the region. Wrought iron was used in the production of railroad tracks, railcars and steamboats, so there were small iron furnace operations throughout the Midwest. Early iron furnaces, structures used to convert iron ore to pig iron using coke, were large stone stacks.

Early iron furnaces were stone stacks- small operations whose locations depended upon iron ore deposits.

Like all of the early industries in the Midwest, iron production was common because of the abundance of locally sourced materials; Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, West Virginia and Pennsylvania had abundant beds of hardwoods, iron ore and limestone deposits. Agriculture, mining and wood product manufacturing were all important to the industrialization of the Midwest, but it was advancements in the iron industry that made transportation development possible, and transportation advancements that in turn made large scale industrialization a reality. This give-and-take between transportation and factory growth/scale was ongoing, and gave rise to the Midwest as the industrial heart of the country.

1850-1900

The middle of the 19th century was marked by the first large scale transformation of the landscape in the still sparsely populated region. The idea of maintaining a ‘Middle Landscape’ was largely forgotten already, and the areas in and around Cleveland, Ohio and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania were at the forefront of iron production in the U.S., transitioning into mass production of steel with the discovery of the pneumatic process and invention of the Bessemer Converter in 1856. This process introduced air into pig iron, removing impurities and allowing the production of steel, as opposed to iron, in large quantities.

The Civil War necessitated production of iron on a larger scale, and the output doubled while the price nearly quadrupled during the war (Casson 3). However, “the greatest need of the world was cheap steel” (Casson 4); iron was cheap to produce, but wasn’t strong enough to support the growing railroad network or other advancements in building and manufacturing. It wasn’t that steel couldn’t be produced, it was that the processes and fuel quantities involved made it unaffordable and impractical.

Wrought iron and cast iron were still considered novel building materials due to high manufacturing cost and were rarely used in architecture. It was used in World’s Fair exhibits- The Crystal Palace was built in 1851 of cast iron, the Eiffel Tower in 1889 of wrought iron, and the Galerie Des Machines of the same year was constructed of iron and steel. In America and Europe, iron was also being used in the construction of bridges and railroads, and cast iron was used for some building façade components. This changed in the last decade of the 19th century, when long-span steel structures started being used for train sheds, notably at Broad Street Station in Philadelphia in 1892. Coinciding with the use of long-span steel structures, major cities began experimenting with structural steel frames, allowing buildings to grow taller.

The pneumatic process, later referred to as the Bessemer Process, paved the way for steel production. William Kelly of Kentucky discovered that air could be used as fuel in steelmaking, and Henry Bessemer of Great Britain perfected the machinery. In 1851, the first converter was built, and “oxygen, which may be had without money in infinite quantities- was now to become the creator of cheap steel” (Casson 6). Steel could now be produced with rapidity and strength at the price of iron.

The following decade brought more advancement in the form of the open hearth furnace, a process which heats pig iron with scrap metal in a furnace to a higher degree than the Bessemer Process allowed, exposing the steel to less nitrogen which can cause it to become brittle. In addition to the mills boosting the economies of cities like Pittsburgh and Cleveland, there were numerous smaller cities and towns that developed around the steel industry in the Mahoning, Ohio, Monongahela and Cuyahoga River Valleys that began as iron works and transitioned into vast complexes capable of mass producing steel. These advancements, combined with new discoveries in the use of concrete, set the following century up for even more rapid transformation.

Beyond steel production, the Midwest was a major manufacturing center. Initially reliant on local resources, the transportation advancements of the first half of the 19th century offered new materials and diversification of products. Furniture production, agricultural machinery, sewing machines, watches and toys were manufactured in bulk, establishing an identity different from that of New England which focused on textile and paper manufacturing. It was during this period that the Midwest surpassed New England, then the Middle Atlantic, and then both northern regions combined in population, but the density was low and the region was still rural. “The availability of land worked against manufactures in two ways: it provided an inducement to agriculture and it dispersed people over an area too large to be a satisfactory market for manufactures” (Marx 149). The struggle to fully industrialize didn’t last very long as the discovery of large ore ranges and coal deposits gave incentive to manufacture locally.

It was in the second half of the 19th century that the Midwest began experimenting with grain elevator materials as a result of industrial growth. Timber, brick, steel and ceramic tile were used before establishing reinforced concrete as the ideal grain elevator material around the turn of the century, when it also began to be used in building design. European Modernists admired the concrete elevators on an aesthetic level; Le Corbusier called them “the magnificent fruits of the new age”, Aldo Rossi later referred to them as “the cathedrals of our time”, and Walter Gropius compared them to the Great Pyramids of ancient Egypt, yet they remain “a scandalously rejected body of major American buildings” (Coolidge).

Grain elevators are innovative, heavily engineered structures, existing as landmarks or way-finding devices and appearing like ‘prairie skyscrapers’ on the flat, monotonous landscape. They were/are “[an] odd mixture of machine and building” (Brown 1) whose internal workings, as described by author Reyner Banham, “seem like a gigantic surrealist architecture turned upside down or like the abandoned cathedral of some sect of iron men”. Their complexities are often overlooked, perhaps because their functionality requires the weatherproofing and durability of the uninterrupted concrete shell.

This was an age when factories in America were still held in high regards because they gave back to the community by providing employment, a higher standard of living, and a social structure. Development and urbanization continued to form around the factory, and some companies established ‘company towns’, where the factory was the center of town and employees resided in homes surrounding it- a system originating in the mining industry. Meanwhile in Europe, accounts of unsafe and unhealthy factory conditions were being published and the smokestack’s appearance shifted from that of a “charmingly picturesque veil” to an “insidious menace” (Darley 32).

1900-1950

Early industrial landscape- American Steel & Wire Co., Cleveland.

The rise of the steel industry, expansion of transportation routes and the increasing population density were symbiotic; advancements in steel manufacturing both made railroad development possible as well as necessitated it, railroad development encouraged more industrial development along its route, and both the railroad and the industry brought population along with them.

While the steel industry helped build the railroad network, it also helped to destroy it with the invention of the automobile. New industries began developing in pockets in the Midwest; Detroit saw the rise of the ‘Big 3’ automakers in the early 20th century: Ford, GM and Chrysler. The first Detroit Ford plant at Piquette Avenue was a Victorian factory building, but Albert Kahn soon became the leading architect of the company and Albert Kahn Associates single-handedly modernized the American factory, as well as factory design throughout the world. Highland Park was designed in 1913 in response to the newly invented assembly line, using new building techniques like reinforced concrete and steel trusses, and Ford quickly moved sites and changed design with the advancing technology.

Giving validity to the idea that factories are the epitome of change, a new Ford complex representing new ideas in terms of both mass production and construction techniques was built in 1917. The River Rouge complex became the most fully integrated car manufacturing facility in the world, consisting of a steel mill, a glass plant, a power plant, and an assembly line. Truly behaving like a city within a city, River Rouge is perhaps the best example of how “factories are the closest phenomena to urban life..” (Darley 135).

With the automotive industry came other industries, such as rubber, which was based in Akron, Ohio, the “Rubber Capital of the World”. In 1950, more than 130 different companies manufactured rubber in Ohio, becoming the state’s largest industry next to steel. These factories became vast industrial complexes as well, producing not only automobile and bicycle tires but also fire hose and rubber tubing.

In 1906, Gary, Indiana was founded by the United States Steel Corporation. “A city will spring into being at the bidding of no God or Demigods, but of half a dozen very practical businessmen” (Sisson). A true factory town, Gary became ‘Steel City’, and contributed heavily to the large number of existing steel mills in the Chicago area. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, Gary prospered as a safe, blue-collar community with abundant work opportunity. Steel production polluted the air, but the quality of life was high and Gary became home to the world’s largest steel mill.

In 1913, Walter Gropius published an essay in which he praises American industrial design, citing the recently completed Highland Park and including photographs of grain elevators from Buffalo to Minnesota. At the end of the essay, he states that these structures bare comparison “in monumental force, to the constructions of Ancient Egypt”.

By romanticizing the exterior of the factory, the grimy realities of factory life could be ignored. However, this ignorance only lasted as long as the factories supported and gave something back to their communities. For Americans, the mental shift away from the ‘picturesque’ smokestack officially occurred during the following periods of deindustrialization.

Effect

Industrialization on such a large scale gave a sense of purpose to the Midwest. It spawned urbanization and identified it as a blue collar, ‘All-American’, hard-working group of people. There grew a strong sense of regionalism among residents who were all ‘from away’ and flocked to the factories to earn a decent wage and to live in “the Midwest as ‘Main Street’” or “America’s collective ‘hometown’” (Shortridge)- a microcosm of idyllic America.

Identity, Culture, Regionalism, Purpose

The region has always suffered through identity crises; the south, west and northeast all harbored specific connotations but the Midwest was lacking in any association until it became the industrial heartland. It was only natural that, upon losing its industry, the Midwest would come to be identified with the decaying state of the very material that brought it into being.